Adaptations

For mangroves to survive in the intertidal environment, they must be able to tolerate broad ranges of salinity, temperature, and moisture.

Mangrove mud is low in oxygen and different species cope with this in a variety of ways. Red mangroves prop themselves above the water level with stilt roots and can then absorb air through pores in their bark. Black mangroves live on higher ground and have large numbers of pneumatophores (specialised root-like structures which stick up out of the soil like straws for breathing) which are also covered in pores (lenticels).

These pneumatophores can reach heights of up to thirty centimetres, and in some species, over three metres. There are four types of pneumatophore—stilt or prop type, snorkel or peg type, knee type, and ribbon or plank type. Knee and ribbon types may be combined with buttress roots at the base of the tree.

Salt levels in the mud can increase signicantly due to evaporation of water at low tide. Some of this salt may be flushed out when the tide returns but mangroves need to be able to cope with higher salinity levels than most plants. Red mangroves exclude salt by having significantly impermeable (not allowing fluid to pass through) roots which act as a filtration system. Analysis of water inside mangroves has shown 90% to 97% of salt has been excluded at the roots.

Salt which does accumulate in the shoot, concentrates in old leaves and bark which the plant then sheds. Red mangroves can also store salt in cell vacuoles (a space within enclosed by a membrane often containing fluid). White mangroves can secrete salts directly; they have two salt glands at each leaf base.

Some mangroves use only one of these methods but many use two or more. In addition mangroves have adapations to conserve water. These include a thick waxy cuticle (skin on the leaf) or dense hairs to reduce transpiration - the loss of water. Most evaporation loss occurs through stomata - pores in the leaves - so these are often sunken below the leaf surface where they are protected from drying winds. Leaves are also commonly succulent, storing water in fleshy internal tissue.

Because of the limited fresh water available in salty intertidal soils, mangroves limit the amount of water they lose through their leaves. They can restrict the opening of their stomata (pores on the leaf surfaces). They also vary the orientation of their leaves to avoid the harsh midday sun and so reduce evaporation from the leaves.

The biggest problem that mangroves face is nutrient uptake. Because the soil is perpetually waterlogged, there is little free oxygen.

Anaerobic bacteria help produce nitrogen gas, soluble iron, inorganic phosphates, sulfides, and methane, which makes the soil much less nutritious and contributes to their “rotten egg” smell. Pneumatophores allow mangroves to absorb gases directly from the atmosphere, and other nutrients such as iron, from the poor soil. Mangroves store gases directly inside the roots, using them even when the roots are submerged during high tide.

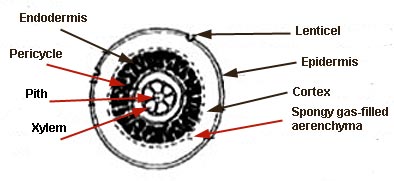

| Lenticel |

A raised pore in the stem of a woody plant that allow gas exchange between the air and plant tissues |

| Epidermis |

The outer layer of cells covering an organism |

| Cortex |

The outer layer of an internal organ |

| Aerenchyma |

An air channel in the roots of some plants |

| Endodermis |

An inner layer of cells in the cortex of a root |

| Pericycle |

A thin layer of plant tissue between the endodermis and the phloem |

| Pith |

The soft, spongelike, central cylinder of the stems of most flowering plants |

| Xylem |

The vascular tissue in plants that conducts water and dissolved nutrients upward from the root |